Oh, So You Use Filters!

If I had a dollar for every time I hear “Oh, you used a filter for that shot,” I’d be retired now, sipping Marguerites on a Pacific island. Of course, that comment is usually said disparagingly, often with a frown of distaste and typically in front of a woman hanging on to her man’s arm. She, naturally, nods approvingly, blissfully unaware of her husband’s profound ignorance.

Many photographers use filters in ‘artistic’ ways in order to manipulate the scene to craft their unique vision. In my work I simply cannot do that. Most magazines require that I shoot a scene as it appears, without radical enhancements. Yet I still use filters. How’s that?

The human eye is multiple times more sensitive than the finest digital sensors, able to discern light areas from dark, even different shades of dark within landscape shadows. If I were to simply meter on the shadows in the scene, I’d end up with an image in which the sky is what we call ‘overblown,’ meaning that there are no details in the bright areas of the scene.

Conversely, if I meter on the brighter portions, the sensor screams ‘Hey, it’s too bright out there, close down the lens opening!’ As a result, the shadows in the scene are rendered so dark there is no detail within them. Trees, for example, will come out as black, featureless silhouettes, which might actually look nice in certain scenes. But frankly, my editors, or those who purchase my images for their homes and offices, would not be pleased if there are massive black areas with no discernible detail.

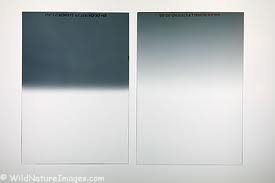

So, in those cases when I have huge expanses of sky and mountains and forest below, I use a special glass or resin filter known as a Graduated Neutral Density. Above is a photo of what it looks like.

The filter has a coating that reduces the light reaching certain areas of the sensor, while allowing full light to come through the rest, all without affecting the color of the scene. Pretty nifty, eh?

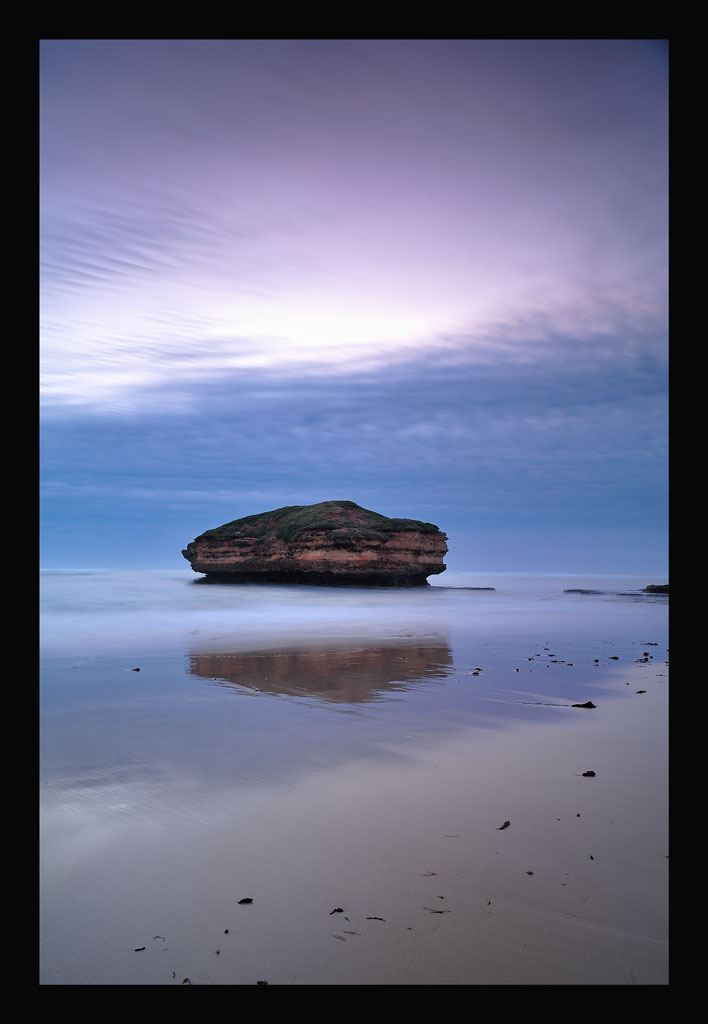

There are technical explanations for how this happens having to do with reducing the dynamic range of the scene, but it’s the results that matter, so I’ll skip the technical mumbo-jumbo in this blog. What the GND filter means is that my images are usually nicely balanced and I avoid blown out highlights, although sometimes you can’t avoid it no matter what you do. Here are some examples where I’ve used a GND filter, almost always when there is a large expanse of bright sky that I have to tame.

Another filter I use a lot is a simple polarizing filter. This filter works like your polarizing sunglasses, only better. Once you screw in the filter, you just rotate the two pieces of glass as you look through the viewfinder and- voila!- magic happens. Clouds seem to almost pop out of the scene. The sky becomes crisp and clear. Distracting reflections disappear from water scenes and the reflections you want are emphasized.

Those are basically the only filters I use, and they are by no means inexpensive. I always recommend that you get the best filters (and lenses) you can afford, since everything we do in photography is done through glass (or resins). I personally use Singh-Ray (www.singh-ray.com) and Lee (www.leefilters.com) filters.