Editing One's Work

I was once asked by an interviewer what I thought the most difficult job in photography is. I have to admit that the question stumped me. Getting up for sunrise entered my mind. Hiking for three days with a 30-pound photo backpack to get a single shot? Telling one’s spouse that you are about to spend $30,000 on a new Hasselblad digital camera system?

In the years since I was asked that question, I have thought about it many times. The answer has changed with experience, but now with more than 50 years experience I have consistently held this answer the longest. In my mind the most difficult thing in photography is editing one’s own work.

The Editing Dilemma

If you think of editing your images as merely post-processing, you are missing the point. Yes, that job can be a chore, especially when you come home with 30K images from a trip to Africa. Also true is that sometimes a single image can frustratingly take an hour or more to post-process “just right”.

After so many decades in the field, my observation is that the real challenge with editing your own work is a mental one. I have seen some of my professional colleagues showcase to me their portfolio and I am frankly stunned at their erratic choices. In most cases I know their work well. I have seen images that I believe are certainly better, stronger and more dynamic. Yet they chose ones to represent their work that are inferior. With amateurs, the situation is far worse. Why, then. is editing so darned difficult?

I think part of the problem lies in how we edit. We normally do it alone, and often after a hard day’s work, when we are tired and our creative senses are dulled and slow to respond. I know that when I struggle over editing an image late at night and I view it the next morning, I often wonder what the heck I was drinking while editing!

Then, once edited, how many of us actually ask for input on those images? I realize that I’m blessed with an assistant (Bob) and a wife (Leslie, an artist) who won’t hesitate to tell me that an image I worked on for an hour looks like s%#t to them. Editing in a vacuum just can’t hold a candle to trusted eyes and artistic sensibilities.

Another issue with editing your own images is doing the hard work of deciding exactly what story it is you are trying to tell. What emotions are you trying to convey? How can you improve the dynamism of the image? Even more difficult; how do the images tie together? How do they portray your unique artistry?

We are often overly attached to an image because of what we went through to capture it. I know I used to be invested in that, trying to make lemonade out of an image that was a downright lemon! Then I read a great quote by George Lepp in which he said that there is really no such thing as a bad day for a nature photographer. No matter what the outcome, we are fortunate to be out in nature, enjoying its gifts. I have hiked in the wilderness for days without a single decent image. I no longer agonize about it. And I surely don’t try to edit the b’jeezus out of those bad shots.

Some Solutions

Bob and I have hit upon a solution that we have proved works. For photographers who already have a decent body of work to draw from, we advise working under the tutelage of professionals, along with colleagues, to vet your work and to then slowly and carefully decide on the ten or twelve images that are truly representative of your very finest imagery.

Not that your tastes, your style, or your artistic vision won’t change as the years go by. That is a given. But once you learn the difficult skills of self-editing, changes are easier to implement.

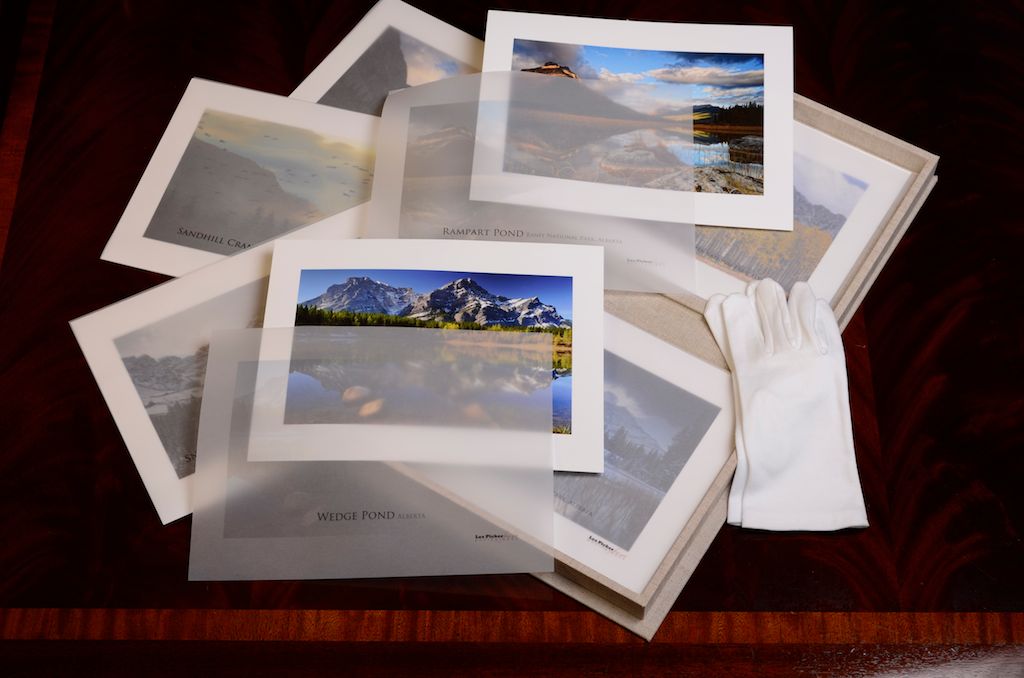

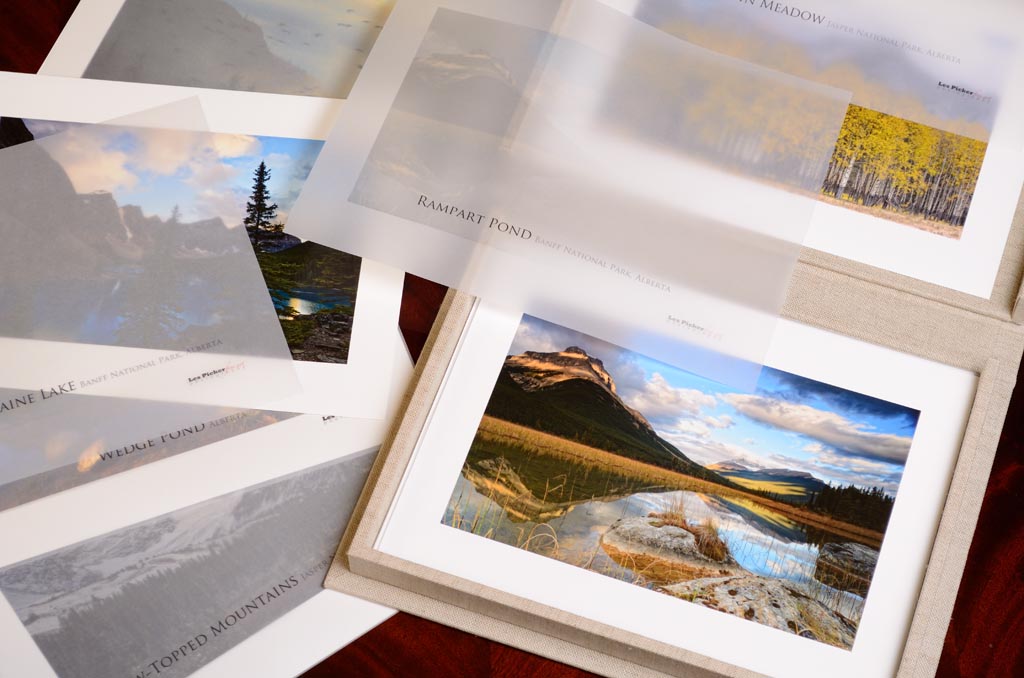

Take, for example, the 3-day workshop we offer each year to just four photographers, carefully designed to result in a gorgeous, hand-made portfolio that can be used to showcase one’s work to editors, family and friends. Yes, that workshop has some defined, professional products at the end that participants go home with but, candidly, that is not our primary goal.

Our principle goal is to teach our clients how to self-edit their work. We start two months ahead of the face-to-face workshop weekend by having each client send us approximately 50 images. Bob an I spend hours going over each set of images, offering critique, making suggestions and helping our clients create a focused portfolio.

During the Friday-Sunday workshop, we work together with the four photographers, offering insights into post-processing, helping them work as a team to come up with the final 10-12 images that will constitute their current best work. Then Bob an I pull an all-nighter, printing their final selections on Moab Fine Art papers (a division of Legion Paper), using our state-of-the-art Canon ProGraf large format printers.

The physical take-aways are quite impressive, but we hope that it’s the mental take-aways that form the basis for photographic excellence moving forward. And there are things you can to improve your self-editing, even without the need to take a workshop.

Some Self-Editing Tips

There are differences between self-editing in general and doing so with the specific aim of producing a professional-level portfolio. But some basic tips apply to both.

Shoot judiciously. This is perhaps the most exasperating issue for most photographers. Being able to fire off 20 frames/second does not mean that is what you should do in most cases. A thoughtful, self-aware approach to photography is the surest route to excellence.

Learn to cull. This is one of the most exasperating issues that confront professionals who are asked to look at another photographer’s images. Do you honestly not see that the image is blurry? Or that in that full length portrait you cut off the woman’s feet? Or that in the prized image you took of the rare eagle the bird is so far away it could be a robin to the viewer? If any of your images have to be accompanied by an explanation or apology, then get rid of it!

Be sparing with online critiques. We have seen time and again instances where earnest photographers post a nice image on an online forum and are subject to unkind comments, flames, and insults. Not only isn’t this helpful, it can be downright harmful. Far too many people have a vested interest in putting another person’s work down. Go figure!

Ask. Research an advanced amateur or pro whose work you like. Ask her to be your “mentor” for self-editing. Show your appreciation. Ask questions, then listen and don’t defend.

Respect Every Pixel. If you are not committed to excellence, you can only get so far in the hyper-competitive world of photography. In your post-processing, remember that every pixel counts.

Take Advantage of Training. Whether in person or online, training opportunities abound. Take advantage of them. Learn from experience masters. In person workshops allow for one-on-one hands-on learning, which I consider the most effective.